Sessions Nine to Fifteen

Having been eaten by a carpet, our heroes find themselves in a nice white marble building with a bunch of exhibits in glassteel cases (the better to stop light-fingered adventurers helping themselves to priceless antiques). After a brief explore and discovering the windows may show a nice sunlit lawn but in fact open onto something much more disturbing, they find displaced college girl Lady Kandor (whose name will swap randomly between Kador and Kandor until I finally edit her token for the final battle of this sequence). She has lost her memory due to a brush with something bad, but our heroes are able to restore it with the “missing” poster from last session. She turns out to have been investigating the same mystery the players are, because she is plucky and takes no shit. She’s also a master of arcane magic (in this case, history-and-education themed bardery).

From here they discover they are in the Museum of Past Ages, a temple of Stolas (god of owls, stars, learning, and herbs) that used to stand on the edge of the demon haunted southern lands before it was apparently destroyed during the early thirteenth age. In fact, it was woven into a carpet for safe keeping (because I like to give players what they ask for as often as possible).

Further exploration determines that the heroes are in the “before history” wing of the museum that leads on to the “first age” wing where they bump into some heretic Stolas priests, who unleash demons from rose-crystal spheres because they are Blasphemous Heretics. After the skuffle, in pursuit of one of the priests, they discover that the Museum of Past Ages is full of what might be described as theme-park rides in which you can experience past ages, but that thanks to demons and magical instability, the exhibits have metaphorically come alive and are eating the guests.

A fight with giant skeletons in an exhibition hall morphs into a fight with actual giants during the Fall of Axis, and leaves the players holding a baby Empress before they stumble back into the “real world” of the temple.

From there, they stumble through the ages heading for the thirteenth and home. In the process they encounter an instructive Hall of the Age of Towers where they learn about the Dark Cultist and the Dark Gods (who may be relevant later) via the medium of slotting-tokens-into-statues-logic-puzzles; fight angry elves while magically disguised as dwarves in a version of the Age of Strife; get caught up in a battle between the Grandmaster of Flowers and the Astrologer in the Age of Flowers – where they learn that in true Star Trek holodeck fashion some of the magically recreated figures in the theme park rides are aware of what is going on; escape to a haunted graveyard in the Age of the Bone Crown; and pursue Stolas heretics through a mildly flooded jungle temple in the Age of Far Travellers before having a showdown with the high priest himself in the Age of Baelfire.

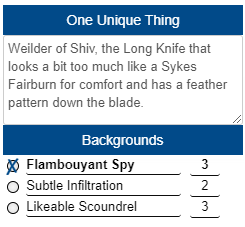

Through all this action, they also pick up clues to a wider story. The Stolas heretics are plundering this lost temple-museum for lore including “stealing” the recreation of the Astrologer. Thomas Gadd encounters the lost Icon of the Hooded Woman who preserved the balance between life and death or something. Grenn learns that he is not the first deadly assassin to wield shiv when someone stabs him with it. Calcifer is educated about the creation of the tieflings and the ascension of the ruler of ancient Turath to become Queen of the Heavens. Dorak gets to smack some elves around. Everyone learns how fragile the Dragon Empire is, and there is some rumination about fate.

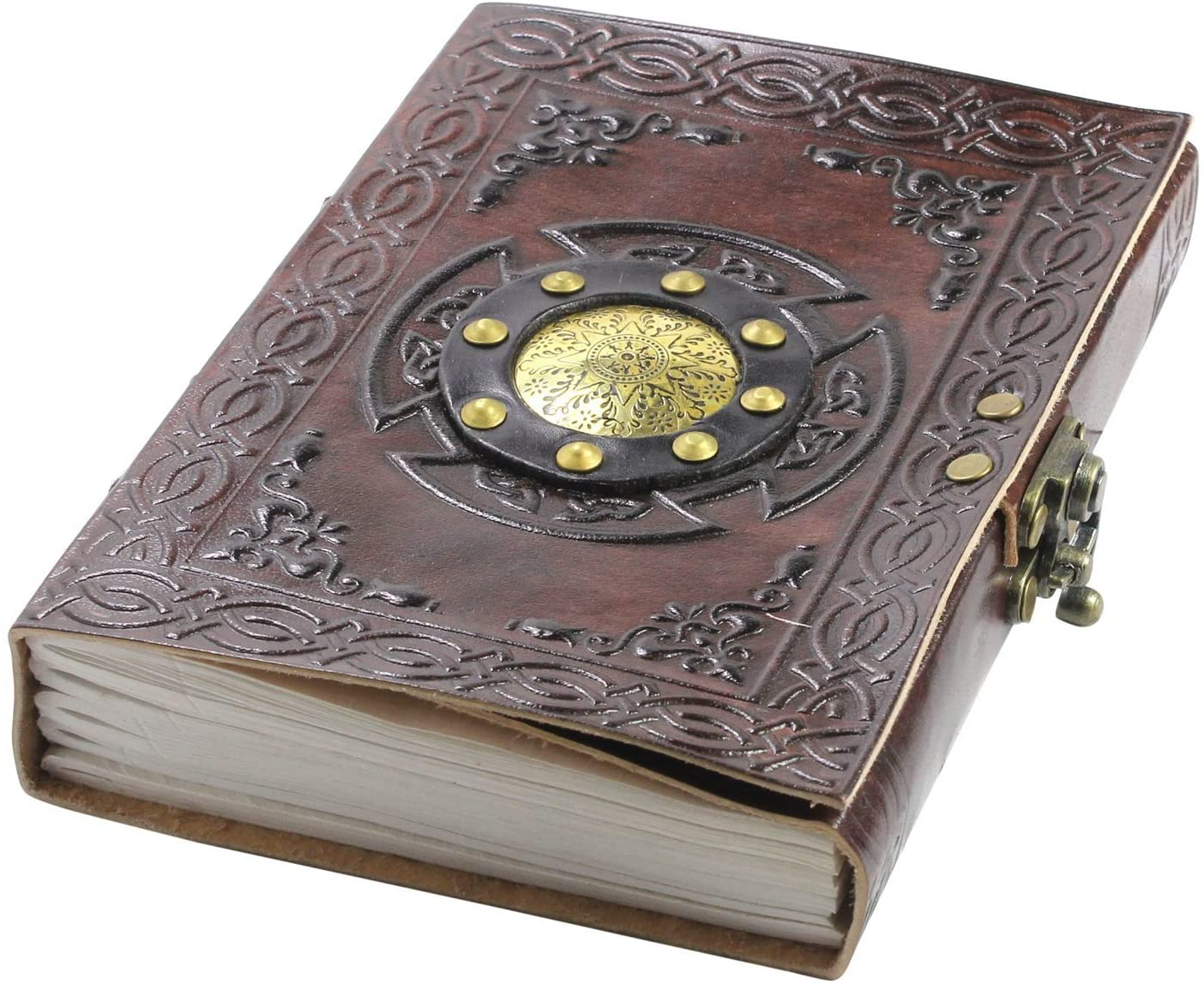

Bursting out of the last portal from the Museum, lightly singed from an encounter with a shadowy copy of an ancient red dragon horror, they discover the temple of Stolas is being purged by warriors of the Crusader, but the timely intervention of people who hate the Lich King (thanks, Icon relationship dice!) they get to safety with Calcifer clutching the second volume of the Book of the Abyss.

Oh, and they also visited the gift shoppe. I forgot to mention the gift shoppe. It was run by an owl-headed angel and they blew a level-and-a-half’s worth of treasure on the most remarkable tat including “cool looking cloaks”, “stuffed animals”, “an unreliable owl oracle”, and a shield with prior-Icon branding. Because of course they did.

The Museum of Past Ages

After a lot of investigation, I decided to run a bit of a dungeon bash with a somewhat old-school vibe. Rather than map out an underground complex, I went for a “theme park” approach. A series of wings each themed around one of the twelve previous ages of the particular 13th Age world I’m running.

Like any theme park, this meant that there’d be a certain railroady element to the encounters, but I tried to mitigate this by putting in clear decision points where the players could decide where they went next to achieve their final goal of passing through the temple and catching up with the corrupt Stolas priests.

My first port of call was the players; I asked them what kinds of things they’d like to fight and got variously “elves”, “druids and bears”, “a dragon” and I think “undead”. Which was helpful.

Then I hit the Book of Ages, and spent a happy afternoon working out my games’ history using the ages defined there. This gave me a very rough road map for the kinds of encounters I’d be running.

Rather than just running a bunch of high-special-effects fights, I also wanted to do some world building and story telling. Notionally, the first sequence of adventures had been about the present (poking around New Port meeting people). The next sequence would be about the future of New Port and it’s politics, so this arc was going to be about the past – not just the past of the Dragon Empire but also to a degree the pasts of the characters.

I knew I wanted some key beats – to show Grenn that his magic dagger has a long history of killing people, to give Calcifer some context for the urge-to-power of the tiefling people, to introduce Thomas Gadd to the Hooded Woman icon who predated the Lich King as the Icon-about-death and see what he made of her, and to give Dorak a chance to hit elves and maybe introduce some King Under The Mountain backstory.

Finally, I still had a list of interesting treasure the players had mentioned they’d like which I wanted to try and pepper through this arc. Oh, and I knew I had roughly twelve significant encounters to do it in as I wanted the players to level to third after the climax.

Building the Museum

The Museum of Lost Ages needed to feel like a sprawling labyrinth of an enchanted building, without my having to design a massive sprawling labyrinth of a building because who has the time for that? With that in mind I envisioned the adventure as a series of bubbles connected with lines. The player characters would move through this field of bubbles in one direction (toward the twelfth age and the showdown with the Stolas priests) and I wanted them to encounter half-a-dozen ages with a couple of them mandatory and some of them where they could choose their direction.

It’s no substitute for actual exploring, but putting two or three crossroads in where the players could decide where to go should help to support the illusion that they were exploring a structure rather than in a mine-cart being taken past the sights. I’d also reinforce this by making sure there were things within the bubbles for them to interact with and poke that weren’t just fights.

This worked best I think in the Age of Towers themed wing, where I had a logic puzzle involving lost cities, Dark Gods, and the leaders they corrupted. Or possibly when the party visited the gift shoppe for a bit of roleplaying with the buff owl angel running it.

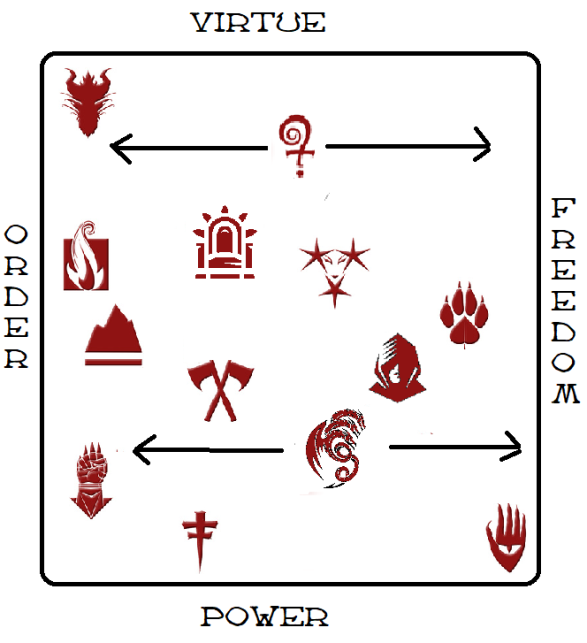

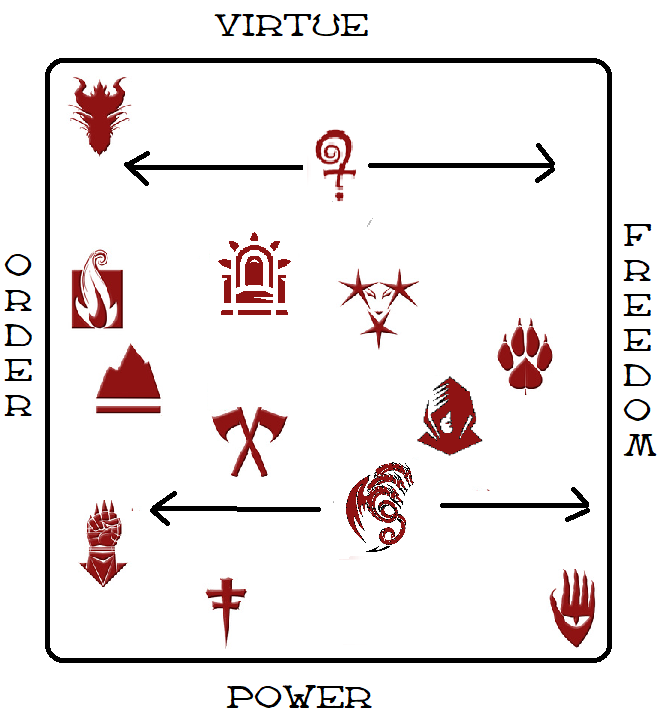

I finished this section off by giving the players a simple graphic showing the “known ages” with easily-identifiable symbols and short summaries of each age. This meant they could make informed choices about things without needing a load of extraneous skill roles, or slowing the action down to explain what each age was.

Setting Up the Fights

With the exception of the Age of Towers puzzle, the gift shoppe pit-stop, and a full heal-up at the camp of the Grandmaster of Flowers and their rebel army, I knew the encounters were going to revolve around fights. We’d chosen 13th Age in part for a chance to have a more “meaty” tactical experience, and I wanted high action and danger to be the theme of this arc. You can absolutely play d20-style fantasy games without a load of fights, but you can also have a huge amount of fun knocking the blocks of bad guys and saving the day with your remarkable combat powers and I was in the mood for some of the latter.

It’s really easy to set up a fight in a game like Dungeons and Dragons or 13th Age. Grab a bunch of monsters from the Monster Manual and have the players hit them. It’s easy, and it can be satisfying, but it quickly gets old. When I’m putting a fight scene together I want more than “players stand toe to toe with monsters alternately rolling to hit and damage” because if I want that I can play Descent instead.

Avoiding Trash Mobs

I don’t use wandering monster tables any more except as inspiration. That isn’t to say I don’t use random encounter tables – but they tend to be weighted more toward “three sinister old women cackle at players” or “a farmer and a fisherman are having an argument” than “1d3 oil beetles attack”. Again YMMV but fights for the sake of fighting leave me cold and unsatisfied. When I’m setting up a fight, the reason that fight is taking place is the first step towards making that fight important and fun.

If you’ve played an MMO, or an old-school D&D module, you’ll probably be familliar with the idea of trash mobs. These are monsters that are just there to be killed, to drop some loot, to pad out the adventure, and to whittle away at player resources. They can be fun. More often, they become frustrating because they just delay you from getting to an actually meaningful encounter.

These days I try never to include encounters with trash mobs. I don’t mean that every fight is a “boss fight” but rather that every fight has a role to play other than just “players fight monsters” in building the world or the story.

As an example I’ll quickly break down the fights from the first arc I ran, where the players fought a sinister rat cult in the sewers.

- The fight in the pub (rats attack the players in a pub): introduce players to combat, introduce Donder and make him useful, present the fact there is a sinister cult of mask-wearing rat-wielding baddies.

- The fight in the cellar (rats): closest to trash mobs, but reinforces that the rat cult has kidnapped the Blue Rose, show that there are unnatural forces at work with the mutant acid-spitting rats, warn the players that acid is going to be a damage theme (something they broadly ignored incidentally)

- The cultists in the sewer: introduce the cult proper, highlight that it is made up of mostly lower-class people, but introduce the university student cultist who will lead into the next arc. Also let people with movement skills show off jumping over sewer channels.

- The giant two-headed mutant rat horror: more mutations, but also the pile of bodies that shows the cultists are kidnapping people, and introduce the wererats and the Rat King faithful who have been targetted by the cult.

- The dwarf skeletons: a change of pace, which also shows-not-tells that New Port is build above an ancient ruined dwarvern citadel that has been consumed by Daaaahk Forces.

- The big showdown: climactic battle against the leader of the demonrat cult, introduce the theme of the cursed books of demon summoning, bring the arc to a close and rescue the Blue Rose.

In every case I try to make sure the players are discovering something during or after each fight. Wherever possible they build on the world lore we’re establishing, and expand on the story we’re telling. In between the fights are other scenes that do the same thing without to-hit rolls or initiative, but every scene in the game has the same basic goal – give the player characters things to explore in a cool way, and move the story we’re creating forward.

A rudimentary checklist

The first thing I do when designing a fight or sequence of fights is ask some basic questions.

What’s the story here?

What does this fight tell us about the adventure we’re on, either through the actions of the opposition, or the nature of the place it’s happening.

The giants in the Age of Founding fight were actually somewhat incidental to introducing a throw-away guard who thrusts the baby Empress into the hands of the players and is the spitting image of their erstwhile companion Donder for example. The fight in the Age of the Bone Crown is really about introducing the idea of white dragons as graveyard guardians and offering Thomas Gadd a connection to the Hooded Woman. Even the very first fight with the Stolas paladins and the rat-demons does a bunch of story development – there are heretic priests here and they are using demonic powers.

The fights are still meant to be cool but the fight isn’t an end in itself.

Why is this a fight?

What’s the motivation of the bad-guys and why might the players be keen to engage with them toe-to-toe? It’s okay for the answer to be “the baddies attack the players to try and stop them” as long as the answer isn’t “they’re orcs and heroes kill orcs”.

The reason for the fight shapes how I think about it – and how I want the players to think about it. There’s a difference between “these murderous thugs want to capture one of your friends and imprison them” and “these town guards think you’re murderous thugs and are trying to subdue you to face justice.”

Sometimes, you can have a fight without actually having a fight. The idea of just narrating a fight is kind-of baked in to 13th Age through the use of montages where one player describes an obstacle and another explains how their character used their abilities to overcome it. I used this during the assault on the stronghold of the Astrologer in the Age of Flowers sequence to add some depth without bogging the game down in trashmobs. The players fought badly-disguised ninjas and some kind of small hydra. On one level it was just a bit of a fun distraction – the characters weren’t really in danger – but it made the experience of assaulting the stronghold more interesting than me saying “You get to the Garden of the Sun and Moon for the important encounter.”

You can even do this a bit more mechanically. Describing or narrating a fight, coupled with either skill rolls or an attack against each character to represent superficial wounds, is basically what I did during the chase through the Manor in session nine. It creates “mild peril” compared to the “full peril” of an actual knock-em-down fight.

What’s cool about this fight?

What stops it being two lumps of hit points rolling d20s at each other? This is different to the story role of the fight. The story places the fight in the wider context of the campaign, but the fight itself still needs to be cool. Sometimes the story role plays double duty “the characters have a showdown with their murderous robot doubles…” is the story making the encounter extra cool. But you can still add “… on the deck of a burning ship!” and make that fight even more memorable.

Does the opposition have interesting abilities, or is there something interesting about the terrain?

What kind of mood am I trying to evoke – is it a fight with a tide of rats in a cramped space, a fast-moving battle through ruins with skirmishing foes, or is there a frikkin dragon that will fly around breathing fire at people and the characters can take pot shots at it with these siege weapons that have been thoughtfully left lying around the place?

Ideally every fight has something about it that sets it apart form earlier fights. This can be easier with a “stunt” adventure like the Museum of Past Ages, obviously, but it’s worth taking the time to find a unique hook for even a mundane fight.

What can players do to feel cool?

Whatever the in-character purpose of the fight, the out-of-character purpose is always the same. The players have fun and feel like heroes. When I’m designing a fight I look for elements I can include that will make players feel clever, or powerful, when they exploit them.

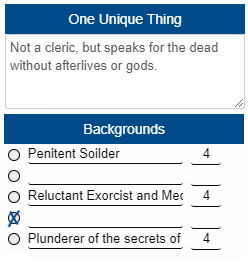

For example, undead opponents will almost always make Thomas Gadd feel cool because he throws holy damage around and that hurts undead a lot, but also because his character is all about ghosts, life-and-death, and sticking it to the Lich King (the source of most undead in the 13th Age I’m running).

A scene with a lot of scenery to jump on or off gives Grenn the rogue more opportunities to show off his movement abilities, but might also give Calcifer the sorcerer-spy some inspiration for a cool stunt, or let a character knock an opponent into a river.

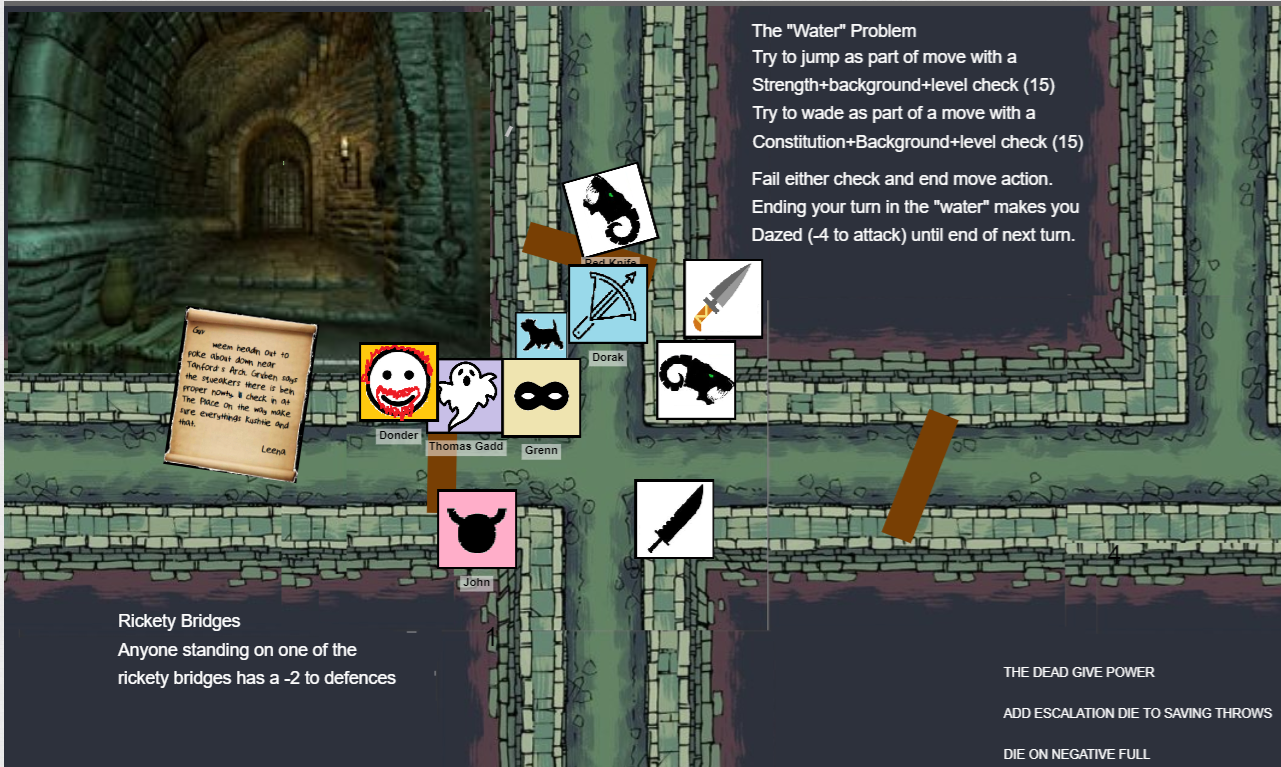

One trick I’ve started using is that after I’ve done all the other prep work on roll20 to lay out an encounter I’ll quickly write a list of a dozen elements that can be found in the scene that will hopefully inspire players to narrate their actions in a cool way. An obvious example was during the climactic dragon-and-high-heretic fight the fact I’d mentioned there were “stagnant puddles” all over lead to Grenn splashing dirty water into his opponents’ eyes as part of his shadow walk maneuver. From past experience, having a written list is a lot more effective than just describing something in that players can look at the words and think about them between turns for example. I might keep it up when I go back to actual tabletop games (assuming I ever do).

Incidentally this emphasis on making the place the fight takes place be as important as the creatures doing the fighting is another reason I dislike random combat encounters. They rarely give me the opportunity to think about where the fight is happening and whats cool about it.

What could go wrong?

What happens if the player characters are defeated? Am I happy for the campaign to end here or is there some way to continue even after defeat? For example, the evil cultists might put the defeated characters in cages intending to sacrifice them to demons giving them a chance to escape. There should still be a cost for defeat obviously – in the sewer-cult-adventure case I’d kill the Blue Rose. In the Museum of Past Ages I’d have the Stolas priests get a step closer to completing their agenda.

I don’t always have to think about this. I tend to assume the players’ characters will broadly be fine in a normal encounter, but it’s something I give some thought to in a climactic enounter or one I know will be tough.

I might find I’ve overstatted, or given a monster an ability that is proving to be unexpectedly deadly. In this case I might tweak the stats so the monster loses access to that ability when they’re on half-hits or less, or have a limited-use player ability turn out to be more effective than expected. In both cases though I try to make sure these tweaks make sense in the context of the fight, and use them when I’ve fucked up or the players are genuinely being unlucky.

The flip side of respecting to your players actions is that sometimes you need to let them reap the tragic harvest of their mistakes. The illusion of defeat is fine, but I prefer to have my players understand that there is a real chance they might be defeated but that defeat =/= tear up your character sheets.

Am I overcomplicating this?

Once I’ve set up the encounter, sorted by stat blocks, and laid out my terrain I take one last look to see if I’ve overcomplicated it. I’ll often realise I’ve put in too many different types of opponent, and that I don’t really need javelin throwers and archers, or that the second stat-block for the cultist acolytes isn’t adding anything except another complicated status effect to the fight.

I also try and make sure that if there’s any special rules in the fight I can lay them out for the players easily. Again on roll20 I’ll add them to the battlefield either was text or as a little card with a cute border. Too many new or random elements can make a fight confusing for the players so I’ll usually restrict myself to a couple. I’ll often fall back on a standardized way of doing things – during the Museum of Past Ages there were several locations where people could fall off or into things, or change their elevation, and I used a standard “climbing or jumping is an appropriate skill DC 15 as a move, or DC 20 as part of a move” to the table.

Even in physical tabletop I’d regularly write out any special rules on a bit of card and stick them near the battle map so players could see them easily. Having this stuff be transparent helps players grokk what is going on more quickly. It’s why things like D&D have “difficult terrain” as a defacto descriptor for everything from undergrowth to pools of water to tiny hurdles. Everyone knows what is going on and can think about what they are doing without getting bogged down in rules discussions.

Building the opposition

This piece is already too long, so I’ll probably talk about “statting the monsters” more in the next thing. But broadly when I’m looking at a monster stat box I tend to think in the same terms as the fight checklist.

What’s the story for this creature’s involvement? Would it make more sense if I reskinned it as a giant T-rex-like dimetrodon?

Why are they fighting? What might cause them to run away, or do something other than fight or make an attack? Can players exploit that?

What’s cool about them? Do they have a signature ability I’ll enjoy describing, or a maneuver they’ll use that players will need to change their tactics to deal with?

How will they make players feel cool? What weaknesses do they have that players can exploit? Will one character be particularly effective against them? If one character finds it hard to deal with them what else is going on in the fight that they can do instead?

What could go wrong? Is their AC or damage surprisingly high? Is there an obviously exploitable way to mitigate that advantage? What happens if the characters turtle, or charge straight in against withering lines of fire?

Am I overcomplicating this? Is this statblock easy to use, is all the info I need at my fingertips, and am I confident I can handle this without slowing the game down? Can I strip out some powers without losing the core theme of the creature? Am I actually going to find it fun to run these monks as if they were PC 13th Age monks complete with their wacky opener/flow/finisher rules that mean I am giving them three times as many options as any other monster in this entire campaign for one fight?

Mark created a Tiefling Sorcerer called “John the Tiefling” – not his real name as he was quick to point out. He had an imp familiar, and he told us that he drew at least some of his power from suspect roots.

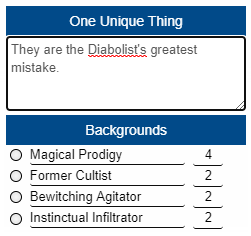

Mark created a Tiefling Sorcerer called “John the Tiefling” – not his real name as he was quick to point out. He had an imp familiar, and he told us that he drew at least some of his power from suspect roots. John likes his 90s tropes, did I mention? When he gave me his One Unique Thing I immediately thought

John likes his 90s tropes, did I mention? When he gave me his One Unique Thing I immediately thought

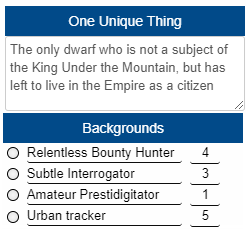

Clive fancied a dwarf ranger. I personally like dwarf rangers as a thing. Much more than I like elf rangers, and not just because I tend to be a bit down on elves in d20 fantasy systems.

Clive fancied a dwarf ranger. I personally like dwarf rangers as a thing. Much more than I like elf rangers, and not just because I tend to be a bit down on elves in d20 fantasy systems. Initially Steve’s character was called “Junn” which he claimed was orcish for “John” but by the mid point of the second session it became clear having two characters and a player called “John” was getting confusing so he “revealed” that Junn was his surname and his real name was Grenn. This brought to an end the brief period in which this game was notionally subtitled “three Johns and a Dwarf” and everyone breathed a sigh of relief.

Initially Steve’s character was called “Junn” which he claimed was orcish for “John” but by the mid point of the second session it became clear having two characters and a player called “John” was getting confusing so he “revealed” that Junn was his surname and his real name was Grenn. This brought to an end the brief period in which this game was notionally subtitled “three Johns and a Dwarf” and everyone breathed a sigh of relief.